Movement in Art – Defining Visual Movement in Art

This post may contain affiliate links. We may earn a small commission from purchases made through them, at no additional cost to you.

Most works of art do not move. However, art that is completely devoid of movement can appear uninspiring and bland. It makes sense that from Impressionism onwards, much of modern and contemporary art has striven to create a sense of compositional ebb and flow. Master artists take pride in their ability to take their viewers on a journey of revelation through their works of art.

Table of Contents

Many artists achieve visual movement in art by depicting motion in an artwork, leading an observer from one section to another, or by making the artwork itself move as a part of the viewing experience. Because of its instinctive appeal, movement is often associated with nature and living beings.

Durchbrochener Fels bei Etretat (Hollowed Cliff near Étretat) (1883) by Claude Monet, located in the Clark Art Institute in Massachusetts, United States; Claude Monet, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Durchbrochener Fels bei Etretat (Hollowed Cliff near Étretat) (1883) by Claude Monet, located in the Clark Art Institute in Massachusetts, United States; Claude Monet, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

What Is Movement in Art?

The movement in art definition is based on the arrangement of elements such as line, color, shape, texture, and pattern. The human eye tends to move most easily along paths of equal value. Movement as one of the principles of art creates a sense of flow in a work of art. It can apply to the whole or a single section within a composition. Visual artists use movement in art to create action or an impression of action, guiding their viewer’s eyes around their work.

The use of movement often directs the viewer toward focal areas.

Types of Movement in Art

There are several artistic techniques for achieving visual movement in art. Movement in art can be seen in many different artworks, in many different forms. There are four basic strategies for creating movement in art and they are implied, actual, sequential, and optical movement. Most of these strategies involve static artworks but many artworks incorporate actual movement.

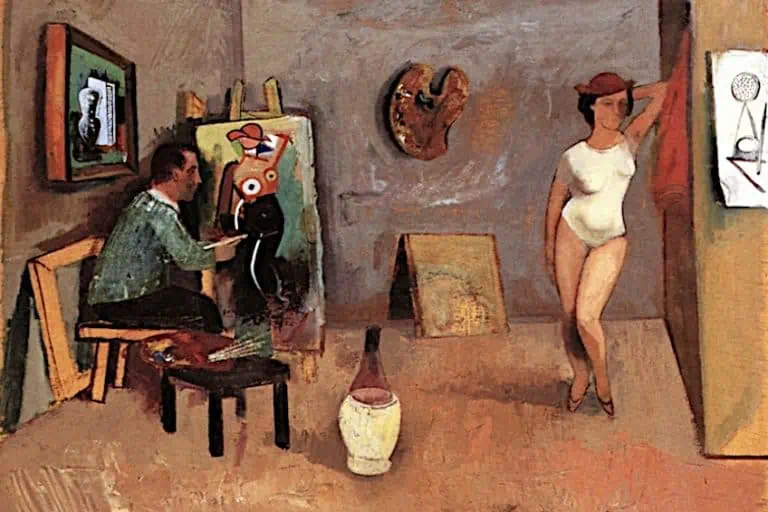

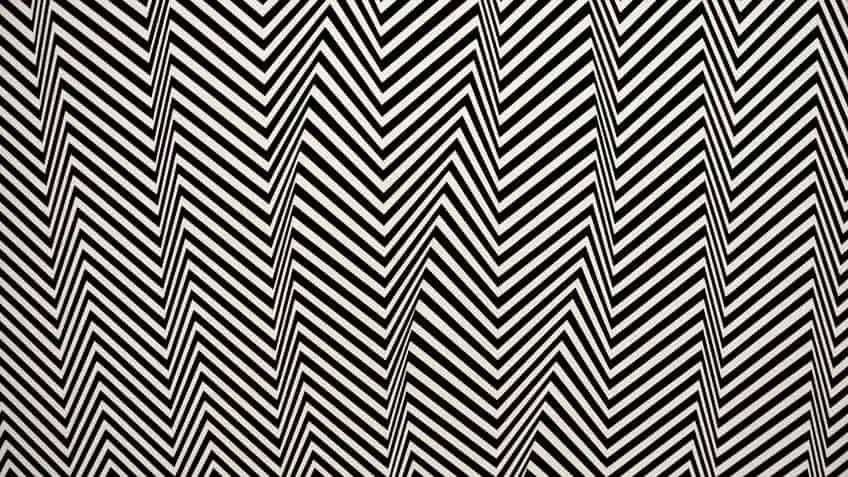

Descending (1965) by Bridget Riley, located in the Kunstmuseum Den Haag in the Hague, Netherlands; Rob Oo from NL, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Descending (1965) by Bridget Riley, located in the Kunstmuseum Den Haag in the Hague, Netherlands; Rob Oo from NL, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Examples of Movement in Art

Implied movement in art applies to static art objects that convey visual movement in art. With this type of movement, the elements are organized so that they lead the viewer’s attention through the composition, from one object or form to one another. An artwork need not be limited to the mere implication of movement. In the context of the movement in art definition, actual movement implies the depiction of something or someone moving within an artwork. One of the examples of movement in art is sequential movement. Sequential movement refers to a repetitive pattern that continues, changing elements progressively. In optical movement, the viewer’s eye is led around a composition through an arrangement of elements such as line and shape.

These mostly non-representational images create complex, illusionistic patterns that challenge the viewer’s perceptive preconceptions.

Implied Movement in Mattia Preti’s Feast of Herod (1661)

| Artist | Mattia Preti (1613 – 1699) |

| Created | 1661 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (cm) | 177.8 x 252.1 |

| Genre | Religious painting |

| Associated Movement | Baroque |

| Location | Toledo Museum of Art, Ohio, United States |

Feast Of Herod by Mattia Preti is a 17th-century religious oil on canvas painting depicting Salomé presenting the head of John the Baptist after his beheading. By placing her in the middle of the painting, Preti emphasizes Salomé’s centrality in the story. Her porcelain white skin stands out and the other figures in the painting have their eyes angled toward her. The peripheral figures who include Salome’s mother and Herod himself, seem to meet eyes, creating a triangular implication. This triangle is what directs the viewer’s gaze through the painting.

Feast of Herod (1661) by Mattia Preti; Mattia Preti, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Feast of Herod (1661) by Mattia Preti; Mattia Preti, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Instead of depicting actual movement, this painting creates the illusion of movement. It directs the viewer’s eye around the composition. The other elements further emphasize the recommended path around the painting. The cloudy sky in the distance, the drapes behind Salomé, and the urns on the steps all lead us down to the lower left-hand portion where John the Baptist’s head is being served on a platter.

Actual Movement in Edgar Degas’ L’Etoile (“The Star”) (c. 1878)

| Artist | Edgar Degas (1834 – 1917) |

| Created | 1878 |

| Medium | Pastel |

| Dimensions (cm) | 60 x 44 |

| Genre | Genre painting |

| Associated Movement | Impressionism |

| Location | Musée d’Orsay, Paris, France |

Degas’ L’Etoile depicts a lone ballerina performing her “pas seul”, leaping towards the orchestra pit. Other dancers, and what appears to be a patron, linger in the wings. While she is en pointe, balancing gracefully on one leg, the dancer’s slanted position is precarious and tense, creating a dizzying sense of movement.

L’Etoile (“The Star”) (c. 1878) by Edgar Degas; Edgar Degas, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

L’Etoile (“The Star”) (c. 1878) by Edgar Degas; Edgar Degas, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The dancer is portrayed bending her head back, closing her eyes, and revealing her rosy cheeks after the sweet success of the performance. Degas’ crisscrossing strokes draw attention to the tension. He paints the stage curtains with a threatening frenzy. The upper-left-hand section of the painting seemingly looms over the glowing triumph of the dancer’s accomplishment. By choosing a moving dancer as his subject Degas captures the unadulterated joy of dance in L’Etoile.

In addition to this, the artist’s combination of fingerprints, shadow, light, dry dabs of color, pastels, sharp outlines, and fluid blurs, compounds the illusion of movement.

Sequential Movement in Marcel Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 (1912)

| Artist | Marcel Duchamp (1887 – 1968) |

| Created | 1912 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (cm) | 147 × 89.2 |

| Genre | Abstract art |

| Associated Movement | Cubism, Cubo-Futurism |

| Location | Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, United States |

Marcel Duchamp’s cubist artwork Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2) is an example of sequential movement in art. Rather than a representational endeavor with meticulous linework and shading, Duchamp’s image is carefully formed from geometric shapes. The artwork features multiple overlapping frames of an indistinct figure coming down a flight of stairs. The overlapping forms in the background appear darker in value and they progressively become lighter towards the bottom right corner, creating an illusion that they are in motion. This illusion of movement is based on the patterns created by the combination of elements. The angles zigzagging through the painting create a downward motion.

The figure is depicted through nested, geometric elements assembled to suggest rhythm through the figure’s self-replication. The seemingly counterclockwise motion mimics rotation from the upper left to the lower right-hand corner, corresponding to the tonal differences seen across the image. The figures in this composition convey movement through their accented arcs and disrupted lines, hinting at a thrusting pelvic motion.

Optical Movement in M.C. Escher Day And Night (1938)

| Artist | M.C. Escher (1898 – 1972) |

| Created | 1938 |

| Medium | Woodcut |

| Dimensions (cm) | 49 x 76 |

| Genre | Printmaking |

| Associated Movement | Op art |

| Location | Boston Public Library, Boston, United States |

M.C. Escher’s Day And Night is a wonderful example of optical movement in that it allows the viewer’s eyes to flow naturally in a specific direction. The simple repetition of elements becomes their metamorphosis, slowly changing from one form to another. Lit in bright white by the daylight, an urban scene with a winding canal running through it is depicted on the left-hand side of the artwork. The converse can be seen on the right side of the painting. From the opposing angle, a night scene depicts a miniature city with a dark canal and black skies.

White birds from the daylight emerge from the center of the landscape into the depth of the night sky, while dark birds flock into the daytime sky. In the center of the image, a bewildering pattern of black and white tiles delivers a geometric positive-negative effect. The forms begin as birds and slowly shift into other forms causing the viewer’s gaze to naturally follow this progression. The use of symmetrical opposites is what draws the viewer in. As a title, Day and Night is on the nose. After all, the composition dangles its viewer between two realities.

The white birds and their bright environment are strongly contrasted by the blackbirds and their dark landscape.

Understanding Visual Movement in Art

Artists can use two-dimensional images to create a sense of movement. But the application of this principle of movement to a static artwork is different from using it in moving sculptures. Static artworks in this case convey the principle of movement to lead the viewer’s attention through a work of art.

Running Along the Beach (1908) by Joaquín Sorolla, located in the Museo de Bellas Artes de Asturias in Oviedo, Spain; Joaquín Sorolla, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Running Along the Beach (1908) by Joaquín Sorolla, located in the Museo de Bellas Artes de Asturias in Oviedo, Spain; Joaquín Sorolla, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Movement in art can be achieved simply through the elements and principles of art. As a prime principle of art, movement encompasses a wide spectrum of compositional techniques, from the depiction of movement to using movement itself in the construction or exhibition of an artwork. Movement transforms a work of art from being decorative to being a dynamic exchange between the artistic expression and the viewer’s psyche.

The Seven Principles of Art Overview

- Principles of Art Overview

- Balance in Art

- Contrast in Art

- Pattern in Art

- Unity and Variety in Art

- Emphasis in Art

- Proportion and Scale in Art

From Modernism, all the way to Contemporary art, movement in art has helped artists articulate their responses to the technological advancements of modern times. Because there is an intrinsic newness to movement in art, it is a key driver of artistic development. Movement in art tends to add excitement, drama, and compositional interest to a work of art. It engages the viewer and encompasses some of the most iconic artistic expressions.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is the Difference Between Movement and Rhythm?

The movement in art definition is often associated with the art principle of rhythm, which is in turn connected to pattern and repetition. When similar or varying elements are repeated in an artwork, this results in a sense of movement. Visual rhythm allows the viewer’s eyes to travel around an artwork, finding points of interest.

What Is Kinetic Art?

Kinetic art is the term used to describe all works that feature movement in art. It describes any form of art that either gives the impression of movement, or uses movement itself as a fundamental feature of the work.

What Is Kinetic Sculpture?

Kinetic sculptures are moving sculptures. Unlike static works of kinetic art, which merely allude to movement in their design, kinetic sculptures involve the physical motion of an art object. Kineticism is an important feature in sculptural traditions of the 20th and 21st centuries.

In 2005, Charlene completed her wellness degrees in therapeutic aromatherapy and reflexology at the International School of Reflexology and Meridian Therapy. She worked for a company offering corporate wellness programs for several years before opening her own therapy practice. In 2015, she was asked by a digital marketer friend to join her company as a content creator, and it was here that she discovered her enthusiasm for writing. Since entering the world of content creation, she has gained a lot of experience over the years writing about various topics such as beauty, health, wellness, travel, crafting, and much more. Due to various circumstances, she had to give up her therapy practice and now works as a freelance writer. Since she is a very creative person and as a balance to writing likes to be active in various areas of art and crafts, the activity at acrylgiessen.com is perfect for her to contribute their knowledge and experience in various creative topics.

Learn more about Charlene Lewis and about us.